Proto-terriers

PRESENTED BY

THE DOMESDAY BOOK OF DOGS

"The cubist effect of square bodies and rectangular heads is due to a temporary modern phase and does not represent a true family characteristic. Generally the group shows marked alertness, activity and propensity to turbulence." Hubbard, 1948.

With few exceptions (mainly Scottish) all the British terrier breeds as we know them originated in the 19th and 20th centuries. There can be little doubt that terriers are bred down hounds, with a huge dollop of blood from other breeds, which themselves would have been bred from an admixture of hunting dogs, water dogs, pastoral dogs and other working dogs. This is an attempt to analyse the breed-types that have existed over the last eight hundred years or so, where known, that may have been added to the melting pot that produced our modern day terrier breeds.

Latham, 1975, has discovered a reference to a terrier from 1211 in the Rolls of King John. As usual there is no description:

"xxiiij brachet, i terreer vj leporariorum"

or: twenty-four hounds, one terrier, six hare dogs.

More recently, still without a description:

Le va quérir dedans terre

Avec ses bons chiens terriers

Que on met dedans les terriers

The above observation on unearthing the fox is taken from Poeme sur las Chasse by Gace De La Vigne (1359), supplied by Hancock, 1990 and Hubbard, 1948, and might translate as:

Go fetch him in the ground

With his good terriers

That we put in the burrows

The above poem is a good example of the origin of the word terrier. As 'terrier' is French for burrow; earth dogs in France were known as 'chien terriers'. The French word 'terrier' derives from 'Terra' the Latin for Earth. In a round about way the term 'earth dog' might also have had a hand in the term 'dog' itself. No one is sure where 'dog' comes from. Canute and the Anglo-Saxons used 'hunt', "rather like the Germans use 'hund'. The Anglo-Saxon 'docga' has been mooted but the Welsh word for terrier, daeargi, could be a more likely source: pronounced 'dye-are-gee' (with a hard 'g'), literally daear = earth and gi = dog. Non-Welsh speakers may have corrupted this to 'dogge', pronounced 'doggy', as English has occasionally adopted words from Welsh and despite the best of intentions the pronunciation has quite often been mangled. This might give us a word trail something like daeargi - doggi - dogge - dog. Writing in the fourteenth century Chaucer used both 'dogge' and the shortened version 'dog'.

|

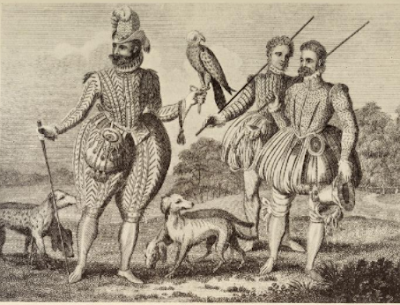

| It was generally accepted in the eighteenth and nineteenth century that the artwork above is a depiction of James VI and I (born 1566). Hackwood. 1907 |

The two pieces of artwork above may well show some sort of progression of the terrier from the late sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century. According to Dutton, 1963, the top artwork is the title page of A Jewell For Gentrie, 1614, a reprint of The Boke of St. Albans, 1486, whereas Hackwood, 1907 captions it 'A Sportsman of the 16th Century'. The dogs in the upper picture 'might' be kenets, a smaller version of the rache. There are several examples of the lower artwork available at the internet archive. This particular picture was chosen because the contrast shows the dogs to good effect. At whatever time the drawing was altered from the original the artist obviously drew dogs with which he was familiar. Two of the dogs have houndy ears and two have terrier-like ears. They could be terriers or terrier/beagle crossbreeds. The dog in the foreground appears to be hound marked.

James I asked his cousin the Earl of Mar for terriers on two occasions. It appears he particularly required terriers of Scottish origin, his first request in August 1617 was for 'two couple of excellent terrieres or earth dogges which are stoute good fox killers and will stay long in the grounde'. His second request came in November of 1624. He asked for four or five couple this time for on-shipment to France and interestingly he said 'which here they calle terrieres, and in Scotlande they calle earth dogges'. He also asked that the dogs should be sent in more than one ship 'leaste one shippe shoulde miscarrie' (Sir William Fraser, 1880).

Occasionally, one comes across anomalies during research on dogs that don't seem to fit with our present day thinking. An example of this occurs in The Sportsman's Directory, 1785, where a description for terrier reads 'A kind of mongrell greyhound, used chiefly for the fox or badger; so called because he creeps into the ground...' The working description is OK but a 'mongrel greyhound' nowadays would be known as a lurcher. The authors may well have only been au fait with dogs of the gentry, whereas terriers and lurchers are, of course, working class dogs. There is another possible explanation - terrier racing. No one knows exactly when terrier racing first became fashionable. 1785 might appear to be rather early but the sport was definitely up and running in the early nineteenth century and to increase the speed of the participants the terriers were hybridised with greyhounds and, some say, the Italian greyhound. There is a suggestion that both the Manchester terrier and the whippet were by-products of terrier racing: could it be possible, just possible, that 'mongrell greyhound', in this instance meaning terrier, is simply a garbled reference to a whippet or at least to a proto-whippet, a breed in development, possibly referred to as a 'snap-dog' during the first half of the nineteenth century. There is, however, a second possibility, that the author has confused the term 'terrier' with teazer or teaser, which could, indeed, be described as 'mongrel greyhounds' as they were hybrids between scenthounds and greyhounds. That this is quite probable becomes obvious when we read the following in the same 'Sportsman's Directory' under the heading Coursing With Greyhounds: "and the terrier, which is a kind of mongrel greyhound, whose business is to drive away the deer before the greyhounds are slipped" - this is a typical description of the working teaser. Elsewhere in the same volume under 'Paddock' there is a brief description of the teaser/teazer at work.

While the origin of the terrier breeds in Britain may be shrouded in mystery, European hunters have been anything but vague. Their usual method was to use bassets as earth dogs. Several French hound breeds have bred down versions. Not large and bulky like the dwarf bloodhound known in English as the 'basset hound', but dogs possibly small enough to go to ground.

During the medieval era the British, Germans and French all attempted to flush vermin in a similar fashion and it may be better to view the development of their earth dogs collectively rather than individually. The demarcation of ‘à jambes droites’ or straight legs and ‘à jambes torses’ or crooked legs used amongst continental basset and dachshund breeders also cropped up for centuries in British terriers. Gifts of hounds, horses and, later, gundogs between the European gentry were well documented but terriers and pinschers could have been toing and froing, unrecorded, across the channel for centuries. Strict anti-rabies controls were not introduced in the UK until 1897. The artwork below, dated 1800, shows two ‘à jambes torses’ amongst a group of three slightly rough-coated, or broken-coated dogs and also possibly two examples of the English terrier, one white, one black and tan (later known as a Manchester terrier). It is a little difficult to tell but these latter two terriers 'might' have cropped ears. The pied dog at the back on the right side of the picture could even be a terrier x turnspit crossbreed.

|

| Cynographia Britannica. Edwards. 1800 |

Lieut.-Col. Smith (1840) considered the wire-haired or Scottish terrier as the more ancient and genuine breed. Saying "Neither of these are crooked-legged, nor long-backed, like turnspits, these qualities being proofs of degeneracy or of crosses of ill-assorted varieties of larger dogs, such as hound, water-dog, or shepherd's dog females, and then perpetuated to serve as terriers."

|

| Scotch terrier. Smith. 1840 |

|

| Isle of Skye terrier. Dogs. Smith. 1840 |

As terriers crawl into an earth their chest circumference needs to be man-spannable, i.e. 14" or less. Smaller offspring might be preferred over their litter-mates in breeding regimes to reduce the size of the proto-terrier hybrids. Standard dachshunds, for instance, have chest circumferences greater than 36cms/ 14ins, yet miniature dachshunds (chest circumference 30 to 35 cms) and the even smaller kaninchenteckels (or rabbit dachshunds, chest circumference 30 cms maximum) were deliberately bred for a chest measurement under 14"/ 36 cms.

Agassian dogs. According to Oppian these were small, unattractive dogs that were used in Britain for hunting. It's a long shot to call these dogs terriers but they did have some terrier-like characteristics. Oppian claimed they possessed ‘remarkable courage’ and excellent nose, noting that 'it is very clever at finding the track of things that walk the earth but skilful too to mark the airy scent.' They were rough-coated and in what may possibly be a reference to crooked forelegs and splayed out front paws (à jambes torses) he described their feet as being ‘armed with grievous claws’. Depending on which translation one uses, Oppian's observation of their mouths is also noteworthy ‘close-set venomous tusks’; if the teeth in the lower jaw were this noticeable it could be that the breed was undershot - in the way that even nowadays some dogs with a protruding lower jaw might have visible ‘tusks’. In 1997 the complete skeleton of a dwarf dog was discovered in a fourth century Romano-British grave in Leicester (Baxter 2006). This dog could have been Oppian's Agassian or possibly a small basset-type introduced by the Romans. In life the specimen weighed about 10kgs, which is exactly the nineteenth century demarcation weight between dachshunds (badger dogs) and dachsbrackes (badger hounds) described by Oberleutnant Jigner, 1902, where individuals from the same litter could end up in either breed depending on their (adult) weight. The estimated height at 26 - 28 cms is also intermediate between the standard dachshund and the Westphalian dachsbracke.

|

| Thornton, 1806. |

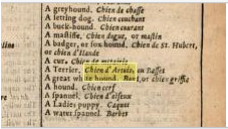

In the mid-19th century, naturalist H. de la Blanchere attempted his own categorisation of the dynamic and ever-changing world of dog breeds (shown below, from Shaw and Stables, 1881). ‘Bassets and terriers’ one of Monsieur de la Blanchere’s subdivisions of hounds (chiens courants) seems to imply he was in no doubt that the Scotch terriers of the time were crooked legged (à jambes torses) and wire-haired (terrier griffon). It is extremely difficult to extrapolate anything at all from M. de la Blanchere’s list but it's nonetheless interesting that a naturalist, a skilled observer, would group terriers with hounds (chiens courants).

|

| After H. de la Blanchere, Shaw & Stables. 1881 (p496). |

The Auld Alliance between Scotland and France lasted for over two and a half centuries and finally came to an end in 1560. Scottish breeds of terrier were held in high esteem and the Auld Alliance could have supplied Scotland with French earth dogs. It's noticeable that Scottish terrier breeds are of the achondroplasic or basset type, i.e. fully formed torso but with shortened limbs. There is a general assumption that the Swiss and Germans owe their short-legged breeds to an influx of French blood; could it be that various Scottish terrier breeds betray a similar influence?

Beagle. Many terrier breeding regimes have used the beagle. The Records of the Old Charlton Hunt, (1910), contains a poem reliably dated to 1737 that advises a cross between a beagle nymph (a small beagle) and a ‘fighting biting cur’ to produce a noisy terrier (necessary when you’re digging to underground combatants).

"Let terriers small be bred...

who choose a fighting biting Curr, who lyes

and is scarce heard, but often kills the fox;

with such a one, bid him a Beagle Join,

the smallest kind, my Nymphs for Hare do use,

that Cross gives Nose, and wisdom to come in,

when Foxes earth, and hounds all bayeing stand."

The artwork below is reproduced here by kind permission of the British Museum. It is by Johannes Stradanus, aka Jan van der Straet, aka Giovanni Stradano, a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth I. Perhaps surprisingly, given the era, the piece is titled The King of England Hunting for Rabbits. Queen Elizabeth I, of course, was a sportswoman of renown and actually hunted her own pack of pocket beagles. The picture is included here as it was referenced by Dansey, 1831, p282. Unusually, Dansey refers to the dogs as beagle terriers but elsewhere in the book he uses the term terrier-beagle; could that means there were two types of dog with similar names. There is no sign of ferrets flushing the rabbits and some of the dogs appear to be about the same size as the rabbits.

|

| Otter terrier. Lomax 1910. |

|

| Scott, 1820. |

Canes wulpeculares. From the reign of King John 1199-1216: "Robert de Ellestede owed six 'canes wulperettos et baldos, et six alios canes wulpeculares,' for a writ of pone against Henry de Saint George ..." Jesse, 1866. The translation of this admittedly 'dog-Latin' sentence might be "six bold fox dogs and six other little fox dogs." 'Vulpecula' translates as 'a little fox', Marchant and Charles, 1946, so presumably canes wulpeculares were little fox dogs. Possibly the same 'breed' as the gupillerettos. Perhaps there were two types of dogs used for exterminating foxes at the time, one larger and one smaller.

|

| Cur chasing fox QMP f.175r |

Cur. Edward, II Duke of York (1413) said "mastiffs that men call curs and their nature, and then of small curs that come to be terriers and their nature..." Curs came in many shapes and sizes, drovers, shepherds and farmers all had their various cur dogs, some like leggy border collies and others rather like corgis or heelers, adept at their work, all useful vermin killers and they could all have interbred with terriers at some point as before dog shows became common the main benchmark would have been working ability and not looks. The bas-de-page on the right, unearthing of the fox, is from the Queen Mary Psalter and has been reliably dated to 1310 - 1320, it may be the oldest reference to terrier work or fox control in existence. The cur (or terrier) in the drawing appears to be slightly smaller than the fox. Lawrence, British Field Sports, 1820, references two types of cur, the vermin cur and the fox cur (probably a hybrid between the foxhound and the cur). Lawrence (1816) recommends kennelling vermin curs with poultry for security reasons: "Several such should be enkennelled in the poultry court, and taught to bark, being equally useful against robbers and vermin" and Lawrence was familiar with terriers and wappets. The December issue of Sporting Magazine, 1805, provides a description of the 'vermin cur': "They were of the true species of the vermin cur, long bodied, bandy-legged, bearded and with mouths of iron." Apparently "they would hunt, attack, and destroy rats, mice, pole-cat, weasel, toad, eft, snake, or viper." Just why newts (efts) would be regarded as 'vermin' is something of a mystery. Symonds, 1881 'translates' the fifteenth century Malvern Chase, the autobiography of Sir Hildebrande de Brute, which is written in Middle English, and fox curs are mentioned involved in a boar hunt where they are used because they have good noses. Wappets and earth dogs were required to be small, if the vermin cur and the fox cur were sizeable dogs perhaps they were the British equivalent of the larger pinschers.

Dung-heap dog. Known as the mist-beller in Germany, the dung heap dog is the myddyng dogge (midden dog) mentioned by Dame Juliana Berners (1486) of Sopwell Priory. Farm watchdog and ratter.

Greyhound. One could do worse than outcross a strain of terriers to the greyhound. This would introduce an abundance of vim, verve and vigour particularly after the Earl of Orford introduced bulldog into the coursing greyhound. That particular eighteenth century outcross was enacted by the Earl to introduce stamina, grit and staying power into his strain of coursing greyhound: any loss of speed could be recovered by simply crossing back to greyhounds over one or perhaps two generations. A greyhound cross would introduce the fire and determination into a strain that is sadly lacking in many modern terrier breeds - working types excepted. A downside of a greyhound cross into a strain of working terrier would be chest circumference, particularly in a first cross, because an earth dog needs to be man-spannable, i.e. 14" chest or less.

Gupileret. Sometimes gupillerettos, Before organised foxhunting the fox was treated as vermin. This dog could have been an earlier terrier as gupilerettis was sometimes used presumably to describe small dogs. Mentioned in a grant from King John 1199-1216 (Maddox, 1769). Perhaps it was the dog shown here helping to unearth a fox. (Goupil being an Old French term for fox). Once described as bonos et baldos (the good and the brave). This may have been the same 'breed' as the canes wulpeculares.

Irish terriers. Terriers from Ireland tend to be somewhat larger than their British counterparts and this seems to have been the case for centuries. "Poets eulogised on the bravery of these dogs and infantry regiments adopted the breeds as mascot. Indeed there is a tale of an Irish terrier bitch that whelped on the back of a mule prior to the Somme offensive", (Plummer 1983). In the last couple of hundred years Irish terriers have certainly been used to standardise some British breeds but whether the Irish dogs were partly instrumental in the development of the proto-terrier is unknown. Glen of Imaal terriers, in particular, could easily be mistaken for a dachsbracke by the uninitiated.

|

| Vero Shaw. 1881. |

|

| Lawrence, 1820. |

|

| Lomax 1910. |

Petits chiens Anglais. Small English Dogs. Along with a type of basset the petits chiens Anglais were one of the two earth dog breeds employed by the Burgundians (Turberville, 1575). We can't be sure what these small English dogs were but it's noticeable that what could have been more 'local' breeds such as early affenpinschers or rattlers weren't used.

Pinschers. Like the terriers the pinschers are the mortal enemy of the rat, some breeds of pinscher were collectively known as rattenfăngers, or ratcatchers (Dr. Z. 1922). Pinschers come in various sizes and the larger ones are too large to go to ground. Being vermin killers they have the typical terrier temperament (or at least they did originally) and possibly developed in parallel with the British and Irish terriers. There is very little information available regarding any interbreeding between pinschers and terriers prior to the eighteenth century.

Ramhunt. Ram-hundt. It is possible that the eleventh century English ramhunt was similar to the wappet. Described as the “dog who watches outside in the rain” ‘Canis qui vigilat foris in pluvia’, Glossarium (1737), the ramhunt was allowed in the forest by King Canute as it was considered too small to harry the King’s deer. According to Canute the breed was small enough to fit into one's lap. Whether it was used for pastoral work or vermin control, or both, is not known. There is a suggestion that 'ramhunt' could be a corruption of 'ren hunt', literally meaning rain dog ('hunt' was the English term for 'dog', thus mirroring the German and Swedish 'hund' and the Dutch 'hond'). Ram hund may be a literal translation of ramdog or sheepdog.

|

| Snap dog with docked tail. |

|

| Hoffman 1901 |

|

| Roscoe, 1808. |

Wappet. As well as mastiff guard dogs - bandogs, tie-dogs or 'great country curs' - many houses (either large or not so large) also had diminutive watchdogs called by various names, wappits/ wapps/ admonishers/ warners/ barkers and canis latrator that, according to Lawrence, 1820, 'might at the same time well earn their daily bread at a country house as vermin-killers' As wappyng was an old hunting term for hounds ‘opening up’ or yapping and barking during the chase we can deduce that the wappet was a small yappy dog: any type of dog would do just so long as it made a racket, and was supple and lithe enough to enable it to hide beneath furniture out of harms way whilst doing so. Sir Walter Scott, who trained as a solicitor after leaving school, was once advised by a client that the best kind of watchdog was not a large dog that was prone to indolence but rather a small noisy dog that was always alert. (Richie, 1981). Oddly enough in North America this 'type' may have been known as the whiffet (Allen, 1852). The wappet/wappit could possibly have been undershot as wapper-jawed means a wry mouth or undershot jaw in some English dialects, although this latter suggestion is unlikely as the wappet was not necessarily a distinct breed.

|

| Chiens terriers et chiens griffons by Alfred De Dreux, 1857. From Drouot 1889. |

Many authors claimed their were two types of terrier and these claims increased in frequency towards the end of the eighteenth century. These authors could have been familiar with terriers but there's a slight possibility that later authors were plagiarising earlier authors; it wouldn't be too far-fetched to assume that the more upper-class writers lacked any interest in terriers whatsoever (not much requirement for terriers on the grouse moors). The terriers, where described, were of two types: one was probably a miniature hound, similar to the modern fox terrier, in form and function if not in colour and pelage. The other terrier was probably a dwarf hound, rough-haired and of the basset type, perhaps similar to the modern PBGV. At the end of the eighteenth century this latter 'breed' may have become known as the vermin cur.

"When I have judged terriers, such as the Sporting Lucas, the Lucas and the Plummer Terrier, I was going over dogs that worked for their living, hunting ground vermin, many of them owned or bred by professional terrier-men. Not one of them was exceptionally low and long, they were not desired to be; they had however the anatomy that allowed them to function underground - an eel-like flexibility based on a strong, supple spine, good forward and rearward reach and a strong loin. If professional terrier-men see no value in exceptionally long and low earth-dogs, why does a KC committee based in Piccadilly think it knows better? If function does not justify the exaggerated form of a breed of dogs and if vets condemn the conformation being sought, how can the endorsement of unusually long and low dogs by the KC justify their declared purpose of 'improving dogs'? If you compare illustrations of Skye, Dandie Dinmont and Sealyham Terriers of one hundred years ago with those of today, I don't think the word 'improvement' is appropriate. Terriers with no leg length cannot move freely. They need free leg movement not castors." Colonel David Hancock MBE on terrier conformation, from Mad About Terriers - Hopping Mad.

In conclusion James Watson, 1906, American show judge and editor of the American kennel register made a valid and pertinent point when he said: "That the terrier was really entitled to rank with hounds is not to be readily disputed, for taking a broad view of the group of terriers, there is more or less resemblance to the hounds that were kept in various districts." Watson goes on to give various examples to bolster this theory and adds: "It seems reasonable therefore to conclude that terriers were small mongrels in which hound blood formed considerable part, and that the rough coats and sprightliness came from greyhound infusions, so there was nothing at all incongruous in calling them half-bred greyhounds or recommending a cross of bastard mastiffs and beagles."

References.

Queen Mary Psalter 1310 - 1320.

British Library, Digitised Manuscripts.

Edward, II Duke of York. 1413.

The Boke of Seynt Albans.

Dame Juliana Berners. 1486.

The Noble art of Venerie or Hunting.

Turberville. 1575.

The King of England Hunting for Rabbits

Jan van der Straet. c1597. British Museum.

Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues.

Cotgrave, Randle. 1673.

The Gentleman's Recreation. 1686.

Richard Blome. Freeman Collins, for Nicholas Cox.

Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae latinitatis.

1737

The Complete Family-piece... 1737

Bettesworth, Hitch, Rivington, Birt, Longman, Clarke.

Forst und jagd-historie der Teutschen. Friedrich Ulrich Stisser. 1754

J.C. Langenheim, Leipzig.

L'école de la chasse aux chiens courants...

Lallemant. 1768.

History and antiquities of the exchequer of the kings of England. 1769.

Thomas Maddox. Vol I. p274 footnote 'l'

The Sportsman Directory; or the Gentheman's companion for Town and Country.

The Best Authors and Experienced Gentleman. 1785.

Cynographia Britannica. Sydenham Edwards. 1800.

C. Whittingham, London

Sporting Magazine. 1805

Rogerson & Tuxford

A Sporting Tour in France.

Colonel Thornton. 1806.

The Council of Dogs, William Roscoe.

Juvenile Library, London. 1808.

A practical treatise ... all kinds of domestic poultry.

Lawrence. 1816. Sherwood, Nealy and Jones.

The dog, his various breeds and varieties, history of its dissemination and destinies, education, use, Diseases and enemies. P55. Ludwig Walther Friedrich, 1817.

British Field Sports... John Lawrence.

Sherwood, Nealy and Jones. 1820.

Sportsman's Repository. John Lawrence.

Sherwood, Neely and Jones, London. 1820.

Arrian on coursing. J. Bohn, London.

William Dansey. 1831.

Dogs. Lieutenant-Colonel Chas Hamilton Smith. 1840.

The Naturalist's Library. Chatto & Windus, Piccadilly, London.

Rural architecture: being a complete description of farm houses, cottages...

Lewis F. Allen. Orange Judd & Company. 1852

The Popular History of England.

Charles Knight. 1854. F. Warne and co. London and New York.

Charles Knight. 1854. F. Warne and co. London and New York.

My Life and recollections. Hurst and Blackett.

Fitzhardinge Berkeley, Grantley. 1866.

Researches into the history of the British dog. 1866

George R. Jesse

The Red Book of Menteith. Sir William Fraser.

Charles Stirling Home Drummond Moray. 1880.

The Illustrated Book of the Dog. 1881.

Vero Shaw, Gordon Stables. Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.

Malvern Chase. Whittington

William Samuel Symonds. 1881.

Tableaux modernes, sujets de courses et de chasse ...

Hotel Drouot. Paris. 1889.

A history and description of the modern dogs...(terriers).

Rawdon B. Lee. - H. Cox, London. 1894.

The Dog: its varieties and management in health. J.H.Walsh.

London; New York: Frederick Warne and Co., 1896.

Joseph Wright. 1898. Frowde, London. Putnam's, New York.

Das Buch vom gesunden und kranken Hunde...

Hoffman 1901

A history and description, with reminiscences, of the fox terrier.

Rawdon Briggs Lee. London: Horace Cox. 1902

Oberleutnant a. D. Emil Jigner

The dog book. Doubleday, Page and co. New York.

Watson, James. 1906. P402.

Old English Sports. Unwin, London.

Frederick William Hackwood. 1907.

Otter hunting diary: 1829 - 1871, of the late James Lomax, Esq, of Clayton Hall.

Blackburn, [Eng.] : T. Briggs. 1910

Records of the old Charlton hunt. Elkin-Mathews, London. 1910.

Charles Henry Gordon-Lennox, Earl of March

Sporting Terriers. Pierce O'conor. 1921.

Reprinted by Coch-y-Bonddu Books.

Berliner Tierärztliche Wochenschrift 38. Dr. Z. 1922

Rattenvertilgung mit kohlensaurem Baryum und mit Hilfe der hunde

Cassell's Latin Dictionary.

J.R.V. Marchant, M.A., Joseph F. Charles, B.A. 1946

Dogs in Britain. Macmillan, London.

Clifford Hubbard. 1948.

English court life, from Henry VII to George II

Dutton, Ralph. 1963. B.T.Batsford, London.

Sport With Terriers. Patricia Adams Lent.

Rome, N.Y., Arner Publications. 1973.

Dictionary of medieval Latin ... 1975

R.E. Latham. British Academy, Oxford University Press.

D. Brian Plummer. 1978.

The British Dog. Carson I.A. Ritchie.

Robert Hale, London. 1981.

Shooting Times and Country magazine.

Irish Terriers. Brian Plummer. June 30 - July 6, 1983.

Terriers of the World. 1984.

Tom Horner. London; Boston: Faber & Faber

The Heritage of the dog. 1990.

Col. David Hancock. Nimrod Press.

The Sporting Terrier.

D. Brian Plummer. 1992

A Dwarf 'Hound' Skeleton from a Romano-British Grave ...

Ian Logan Baxter. Researchgate. 2006

The invention of the basset hound: breed, blood and the late Victorian

dog fancy, 1865-1900. Worboys & Pemberton. University of Manchester. 2015.

Mad About Terriers - Hopping Mad.

Col. Davis Hancock. MBE.

SEE Dachshund

SEE English terrier

SEE Herdsman's cur

SEE Lurcher

SEE Prick-eared cur.

Comments

Post a Comment